| world-class \ˈwərl(d)-ˈklas \ (adj) being of the highest caliber in the world Merriam Webster |

We’ve all heard the accolade “world-class” attached to various people. Athletes, surgeons, musicians, chefs, anyone performing at the highest levels of their craft.

I never gave a moment’s thought to anything in MY life being world-class until recently.

I was listening to an episode on the Tim Ferriss podcast. His guest was Ann Miura-Ko, a technology-startup investor as well as lecturer on entrepreneurship at Stanford.

She grew up in a very traditional Japanese family (i.e. driven by education, effort, and excellence) in which her father’s common refrain throughout Ann’s childhood and adolescence, to check whether her work had met the family standard of quality, was to ask, “Is that world-class?” A tough metric by which to be measured, but that was the expectation. World-class effort.

Ann shared a story about her work-study job at Yale. She was basically an office grunt for the Dean of Engineering. When she called her parents before her first day on the job, her dad reminded her to do world-class work. She was like, Um, pretty sure photocopying and filing is not world-class stuff. But then, standing in front of the copy machine, she couldn’t help thinking: What would world-class photocopying look like? Perfectly aligned pages, crisp and neat, color-matched exactly to the originals. What about world-class filing? Coffee runs? She decided to bring an effort and mindfulness to her work, tasks that many might have said didn’t really matter. Her “world-class” office work was noticed by her bosses, but even if it hadn’t been, it mattered to her to feel proud of the work she’d done.

I was very inspired by that philosophy. I do so many things on autopilot, or put minimum effort into tasks that seem insignificant. And maybe not everything I do has to be world-class, but it got me thinking, what if MORE of the things I do were? If I’m bothering to do something, why not try to do the thing as best I can? Show a bit more care? Go just a little above and beyond? Find a way to take something “small” and turn it into something special.

I think we kid ourselves when we take comfort in the knowledge that nobody else will witness our shoddy work or half-assed efforts. I think, whether we consciously acknowledge it or not, all that half-effort accumulates and erodes our sense of self-respect. Whether anyone else will ever know, WE know whether we’ve tried hard or not. It feels good to do your best at something. It feels kind of crappy to know that you slacked off.

It’s probably not realistic for every aspect of your life to be world-class. Sometimes it’s fine if things are good enough. You can drive yourself into the ground if perfection is the only acceptable outcome for all of your endeavors, and I do not have the energy for that. But I enjoy turning that world-class lens on different aspects of my life:

- What does a world-class teacher look like?

- What would it mean to be a world-class wife?

- Did I do a world-class job cleaning the bathroom??

Just asking the questions and reflecting on the answers is a worthwhile practice. I’m not a fan of the word “mindful” because it is so overused, but it is the perfect word in this case to describe taking that pause to consider the why and how of what we’re doing.

“World-class” has become sort of a thing for me and my husband. We use it in a kidding-not-kidding way, to acknowledge each other’s efforts and shine a light on people whose hard work we admire.

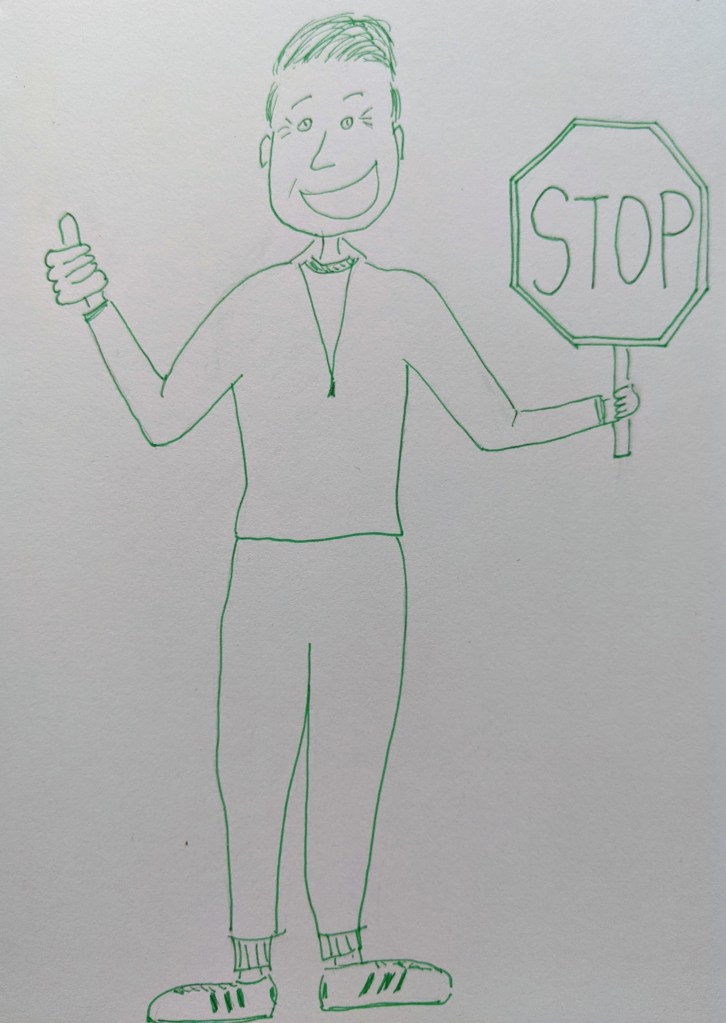

Like this guy:

There is a crossing guard at the elementary school I drive past every day on my way home. He’s in his 50s or 60s, possibly an early retiree who enjoys having a little something to do in the afternoon each day. He’s been doing the job for several years, and every time I see him, I marvel at his energy and enthusiasm. He cheerfully greets the children by name. As he stops traffic to usher the children across the road, he lets the kids jump up and “high five” his stop sign as they pass. He then jogs back to the side of the road so that traffic can resume, but always gives the passing cars a smile and thank-you thumbs up. It makes ME happy to see him each day, and I don’t even know him!

After listening to the podcast, it hit me: That’s a world-class crossing guard!

What stories can you share? Who is doing world-class things in your life?